Here is chapter two of my book, Free World Theory, the final draft. It takes about 10 minutes to read. I’ll post chapter three at the end of the week.

Free World Theory

Chapter Two

by Chas Holloway

2.1

Hierarchies

When it comes to organizing people, there are only two ways possible. The first is hierarchical — which looks like a pyramid. It is how armies are organized, or bureaucracies, or corporations.

A social hierarchy is defined as:

Social Hierarchy

A system in which people are ranked one above the other according to status or authority.

The whole point of organizing people into a hierarchy is for one person (or small group) to have control over the organization. This person gives commands, from the top down. The President, the General, or the CEO wants total control of the organization like he is driving a monster truck.

In a big hierarchy, of course, the leader does not have time to manage details, so he delegates. The next level down delegates to the next level, and so on. As commands go down these organizational rungs, subordinates are expected to follow orders. Most corporations and all nation states and militaries are organized this way.

But anybody who has worked in a giant hierarchy (like government) knows that a leader does not really get total control as advertised. This is because big hierarchies have built-in information-flow problems.

Top down command control is inefficient and this just has to be tolerated.

People at the top and people at the bottom don’t understand each other’s agendas, so information gets garbled.

The further information has travel through levels of hierarchy the more corrupted it tends to become.

When hierarchies get overloaded with people and departments, they become slow and stupid, and cannot react to external conditions quickly.

In the corporate world, companies have to control expenses, so hierarchies are periodically restructured. They fire people, they combine or eliminate departments. But in the political world, in which there is no need for efficiency or accountability, hierarchies just get bigger and bigger. You get bureaucratic bloat.

This is a grave problem today in how society is managed. No matter how hard they try, politicians cannot control it with bigger and bigger bureaucracies. They just make social systems more inefficient. Yet, all over the world, in every nation, huge, unproductive government hierarchies are the single largest “organizers” of society.

This is one reason why political systems and confused and seem to be breaking down, today. The amount of control that central governments want to have over society has exceeded the capabilities of the pyramid organizational scheme. The control capability of social hierarchies is limited by laws of physics. Yet, the rise of Information Age technology requires more speed and efficiency.

Networks, on the other hand, work differently.

2.2

Networks

The second way people can be organized is through a network. Whereas a hierarchy looks like a pyramid, a network has a completely different appearance. Imagine all the fibres of a nervous system. Or imagine you are inside a vast 3-D spiders web. That is what a network looks like.

A network is defined as:

Network

A peer-to-peer system for the purpose of exchanging property.

Unlike hierarchies, in a network there is no “top.” The king does not exist. There is no “boss” or “CEO” or “President.” But there are centers.

The concept of a center is different from the concept of a top. Networks of people have lots of centers. In fact, every place people come together to exchange something is a center — and these centers (and their connections) appear and disappear all the time.

The essential difference between hierarchies and networks is this:

Hierarchies use command control.

Networks use negotiated control.

In a hierarchy, Mr. A says, “Here’s an order, now do what I say,” and Mr. B is expected to obey. In a network, Mr. A and Mr. B mutually decide on a way to exchange property.

This bring us to another big problem in how civilizations are managed today. Instead of networks and hierarchies working together to organize society, they are two conflicting trends. On one hand, government bureaucracies are getting bigger and bigger and trying to centralize social systems. On the other hand, digital culture is rising and its trend is to decentralize social systems. This has created a world in which centralization is at war with decentralization.

This is a clash of two civilizations. It is a direct confrontation over how all of humanity should live.

2.3

Control

How do you control society? This is the biggest question for politicians. How do you control crime? How do you control the economy? How do you control companies from becoming too powerful? How do you control hostile nations? Politicians today even ask, how do you control the climate?

To know how to control things, all you have to do is turn to physics.

Cybernetics is a science created by Norbert Wiener around 1948. It is the study of control mechanisms. A simple example a control system is the thermostat in your home. A thermometer detects the room temperature is below 72 degrees. That condition sends an instruction to a switch which turns on your heater. The heater runs until the thermometer detects the temperature is above 72 degrees, and that condition sends an instruction to switch the heater off again. This process repeats over and over and the temperature in your home stays within a range that is approximately 72 degrees.

Scientists know a lot about control systems. But political governmenta cannot make use of it. There is a BIG obstacle. Large societies today are all hierarchically organized and information flow is too inefficient. The bigger the government pyramid, the longer it takes a signal to move through it, and the more the signal gets garbled.

Even if a politician knew how to control a social problem (they don’t) by the time his or her command worked its way through the system, it would no longer be relevant. Then, the same slop exists in the return signal. No wonder society today is “out of control.” A politician trying to control the changing forces of society is like a drunk trying to race in the Daytona 500. Reaction time is too slow.

Control in a large network, in contrast, is more streamlined. Every time two or more people come together and mutually agree on the terms by which to trade something, a little bit of control happens. Tiny control points exist everywhere. In a large society, billions are occurring simultaneously. All these negotiated exchanges (or decisions to not exchange) create a massive amount of control.

Principle

Voluntary negotiated exchange (or the decision to not exchange) creates a control loci.

The truth is, large networks have far more control built into them than big hierarchies, it is just distributed.

Once again, there are only two ways of organizing societies of people, through hierarchies and through networks. There are no other possibilities. So, let’s compare these two organizational schemes:

In a hierarchy, control originates from the top and “trickles down.”

In a network, control happens whenever two or more people come together and agree on terms by which to exchange property.

In a hierarchy, there is one command point at the top of the pyramid; the controller of society is big and obvious.

In a large network (like the economy), there are billions of tiny bits of control happening all over the map, but because it is distributed, the control is almost invisible.

In a hierarchy, control tends to come from far away, through many layers of bureaucracy; signals therefore collect noise.

In a network control happens topologically closer to where it is needed, so signals are followed more efficiently and tend to not get garbled.

I am not saying that networks are better than hierarchies. I am only pointing out that each scheme has its own strengths and weaknesses. These need to be understood if each type of organization is to be used effectively.

Hierarchies and networks are the two primal ways of organizing people. They are equally important. They are equally necessary. They have both always existed, and they will both always continue to exist.

2.4

Visual Representations

Networks are commonly misunderstood. Today, digital technology is all the rage so people have tried to extend the concept of “network” to describe everything. For example, look at these popular visual representations of so-called “networks” which are currently circulating on the web:

The artist who drew these claims these are six different kinds of “networks,” but only three of them really are: numbers one, two and six. The artist isn’t capturing the essence of what a network of people is, which is a social system in which there are no hierarchies and in which people use negotiated control.

Here’s another group of illustrations:

Likewise, whoever drew these three configurations calls them a “centralized network,” a “decentralized network,” and a “distributed network.” But only the “distributed” is really a network. The others are centralized and hierarchical: they show top-down control. Once again, the artist hasn’t captured the essence of what a social network is.

Here is a better illustration of a network:

And here’s an another interesting one:

In this illustration, why aren’t all the spheres connected up? Because in a network, centers and connections appear and disappear all the time. Any illustration of a social network is only a snapshot at an instant in time.

2.5

Tradeoffs

Neither of these two primal ways of organizing society, the pyramid or the network, is more important than the other. In every society they have both always existed, and they will always continue to exist. But it is important to understand that they each have different strengths and weaknesses. For example:

Goals:

Hierarchies are for accomplishing goals. A leader sets an agenda. He points his people in a specific direction, organizes his team, and says, “This are our priority; we must accomplish X.” In fact, the very word “organization” is defined as:

Organization

The arrangement of assets in order of importance to a goal.

If you want to capture the city, build an industry, elect the candidate, make a big change in the world, building a hierarchy –- a company, a foundation, a military, or a religion –- is how you do it. You put together a team to get something done.

Networks, on the other hand, cannot do this. They have no leader at the top who can point people and assets at a specific goal. Big decisions are not made by one person. In a network, many people make small decisions in their own separate interests, constantly.

What about “terror networks?” Islamic terror nets, for example, have the single goal — that of destroying western civilization. Isn’t this an exception? Actually, it is not. Terms like “terror net” and “terror cell” are just media buzzwords.

Islamic terrorists in America are soldiers behind enemy lines. They assimilate into society, lash out, kill people or blow something up, but they are not acting on their own, or in their own interests. They have been programmed by and are working for a hierarchical religious theocracy.

They are organized insurgents, and insurgency is a tactic as old as war, itself.

Innovation:

Hierarchies are for innovation. For example, a leader of a chemical company directs his organization to create new nutrients for the ag industry. Or Steve Jobs directs Apple to develop the smart phone. If you want to create something new, you are either a lone inventor in your garage or you are the leader of a team.

Networks cannot do this. They dont create new things that change the world, they absorb and integrate changes. Networks are not for innovation, they are for stability.

What about social net companies, like Meta, or TikTok? Aren’t they networks that changed the world. Actually, they are not. Meta is a typical hierarchical company that created a product: Facebook, a social network with particular capabilities and rules that people like to use. That is no different from the Ford Motor Company, making cars.

Speed & Efficiency:

When well-run, small and medium-sized hierarchies can be tremendously fast and efficient. But big ones, no matter how well they are run, tend to be slow and inefficient. The U.S. government, for example, the biggest hierarchy the world has ever seen, is a crazy monument of inefficiency.

The same happens to companies when they grow too big. Efficiencies deteriorate. Mass marketing replaces innovation. Visionary R&D is farmed out to scrappier little companies which can be bought. The ability to adapt to changing external conditions declines.

When the original innovators are gone, the executives who replace them tend not to be as interested in innovation as much as preserving the status quo. The pursuit of new ideas is replaced by the pursuit of government contracts and market dominance. Executives want to believe in an unchanging world that keeps them in power eternally.

These tendencies, combined with increasingly inefficient information flow, is why companies die — think Kodak, Sears & Roebuck, NBC and RCA. It’s why innovation in Silicon Valley has come to a near standstill today.

Networks, on the other hand, are the exact opposite. Small nets are slow and inefficient. But big networks, are amazingly fast and super-efficient. The economy, the internet, spoken languages are examples of superadaptive, super-efficient mega networks.

Ideas that hold civilization back don’t exist. Conservatism and dogma cannot survive in a big network.

Durability:

To an outsider, big hierarchies look strong and indestructible. The U.S. government, The North Korean military, the Soviet Union all look like timeless monuments to the ages. They appear that way because they have a lot of assets under prominent central command. But, ironically, they never survive as long as a network. Every army, government, and nation state that has ever existed has collapsed. Companies have a limited shelf life, too.

Edward Gibbon wrote a book in 1776 called The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. He could have written a thousand sequels and called them, “The Decline and Fall of Fill-In-the-Blank,” because not one empire has ever survived. Hierarchies may look impressive, but they are very temporary.

Networks, on the other hand, last forever. In the history of human civilization there are two legacy networks — social nets, which date back to the beginning of language, and trade nets, which date back to the beginning of settled agrarian culture. Every time there has been a war, a fire, an earthquake, or some other catastrophe, and the nets get scattered to the wind, as soon as the destructive force is gone, they come back together again like the robot in Terminator 2.

Once a people-network exists, it lasts forever. But nation states rise and fall on this planet like weeds.

Scale:

Do you know why giant bugs dont attack New York, crushing buildings, mangling trains and eating commuters, like in the 1950s sci fi movies? Bugs are limited in how big they can get by the laws of physics. The square-cube law (discovered by Galileo) says that when a shape grows in size, its volume expands faster than its surface area. If a bug gets too big, its exoskeleton cannot support its own weight and it cannot take enough oxygen into its bloodstream to supply its own mass.

350 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period, things were different. Bugs were bigger. For example, there was a dragonfly-like creature, called Meganura, with a wingspan of five feet. It could exist because the level of oxygen in the atmosphere was higher then, around 35 percent. Later, as the amount of oxygen in earth’s atmosphere declined to what it is today, around 21 percent, these huge bugs became too inefficient to survive, and they died out.

Bugs did not go away, however. They just got smaller. They are no longer the dominant species on earth, but they are still everywhere doing their part for the ecosystem. They simply adapted to their most efficient scale, and found a new niche.

The very same thing is happening to political hierarchies, today. Gargantuan political bureaucracies are like big bugs getting slower and stupider because the oxygen has drained out of the air. Take a look at this absurd diagram:

This is a government published illustration of how the Obama-era “Affordable Care Act” was supposed to work. Note that every circle and square and diamond on this chart are separate hierarchical bureaucracies. In the center, the big circle is one gargantuan hierarchy imposing top-down control on all the others. This is an attempt to control the entire health care industry, roughly twenty percent of the U.S. economy, using top-down control.

Try to imagine this diagram in 3-D, the center circle high up at the top of a hierarchy, and all the other shapes cascading down. It becomes an immense pyramid with the Master of All Healthcare at its summit.

Humongous bureaucracies like this do not have the evolutionary advantage, anymore. When it comes to large-scale social systems, the advantage today goes to the networks, which are fast, agile, and are constantly self-correcting the details of their operations.

This does not mean that social hierarchies will go away. They won’t. Social pyramids have always existed and they will always continue to exist. But like Carboniferous bugs, they will adapt to their most efficient scale and will no longer be dominant.

2.6

HDS Vs. NDS

Nation states today are all trying to do the same thing: Create government bureaucracies big enough — they hope — to “control everything.” As the digital age hatches strange, new creatures like the world wide web, Bitcoin, Ethereum, smart contracts and DAOs, politicians want to put them under central control, as well.

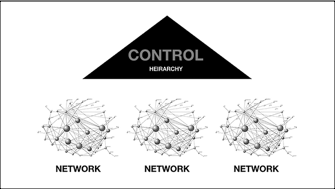

Here is an illustration of the political bureaucrat’s world plan: Total control of all networks by a gigantic government pyramid, like this:

This is the centralized government plan. In Free World Theory, this

is called the Hierarchically Dominant Society (HDS).

Politicians believe this is the just natural way of things. Somebody has to be in control and this is how it has always been done. Historian, Will Durant, wrote, “[long ago] men decided it was better to pay taxes than to fight amongst themselves; better to pay tribute to one magnificent robber than to bribe them all.”1 Why should anything change?

The problem is, the HDS plan cannot be done. No matter how many laws they pass, no matter how much media they buy, no matter how much fear they create or how ruthless they act, the HDS plan no longer works. Politicians are losing control of society. They cannot legislate a slowdown in scientific progress.

They might as well pass a law to stop Jupiter from orbiting the sun.

Fortunately for civilization, there is another way to manage society. Instead of giant government pyramids dominating everything, including the networks, it happens to be the exact opposite. Networks can dominate the hierarchies, and this is already starting to happen. The world we are entering into looks like this:

The Network Dominant Society (NDS).

We are living in a revolutionary time. Social systems that have existed for thousands of years are collapsing. Because of the rise of science and the Information Age, old systems are no longer viable. They cannot function anymore. The age of kingdoms, theocracies, parliaments, politburos — which are all HDS programs — is coming to an end. Human civilization is emerging from a multi-thousand-year-era in which hierarchies dominated society and it is entering into a age in which networks dominate.

This, of course, is massively disorienting, and people want to know:

How can networks coordinate all the myriad activities that go on in a complex society?

How can networks provide national defense?

How can networks stop crime?

How can networks assure that people live in freedom instead of tyranny?

How can networks provide people with security?

How can networks do any of these things when, as I have pointed out, no one is in charge of running them?

Answering these questions is what Free World Theory is all about.

END OF CHAPTER TWO