Here’s chapter Five of Free World Theory. This is the last part of the book that will be available to non-paying subscribers to this Thinkopolis substack. Writing books is a lot of work and no sane person would be willing to do it for free. Hey, $6 per month is a bargain for learning how to create freedom for the first time in history. Help stop the fall of western civ and subscribe by clicking on the blue button, below.

When you subscribe, you’ll also get access to The V-50 Lectures by Jay Snelson, Course V-50 by Andrew Galambos, presentations by Robert LeFevre, and more, all of which are predecessors to Free World Theory.

Free World Theory

Chapter Five

by Chas Holloway

5.1

Slavery, Stealing and Liberty

The definitions in Free World Theory are precise. Every word has an exact meaning. There are no superfluous terms. Each definition contains concepts that fit with the concepts in other definitions. All together, these definitions form a powerful intellectual system, and this book is carefully organized to build that system up, piece by piece.

I said earlier that scientific concepts have to be precise and clear. But that’s not all there is to the story. Let me expand on what I mean by science. By “scientific concept,” I mean “an intellectual model that represents something in the physical world that can be verified using the scientific method.” This is different from pure logic, which is not empirical.

When you study logic, you learn about different kinds of definition — categorical, lexical, ostensive, nominal, and so on. But the definitions I use in this book are none of these. Why? Because it has been demonstrated (by coffee-guzzling epistemologists) that these traditional forms of definition have no hard scientific value. More about that later. For now, I will just say the definitions in Free World Theory are all operational, a special type that does have hard scientific value. They denote concepts that can be physically measured and tested using the scientific method. In science — and this is a science book — that is a big deal.

So, let’s get down to the nitty gritty. The first step in defining freedom is to define its opposite. So, here is the Free World Theory definition of slavery:

Slavery

The control of an individual’s property without his or her consent.

As we’ve discissed, there are four types of property — four kinds of things a person can own. They are 1) one’s biological life, 2) one’s mind, 3) one’s purposeful human actions, and 4) the tangible products of one’s actions. If Mr. A has any one of these being controlled by Mr. B without A’s consent, then Mr. A is being enslaved.

This is not how most people (or governments) view slavery. They tend to think of slavery in a much narrower sense. Most people think of it as the loss of liberty, which is defined as:

Liberty

The ownership of one’s actions.

Loss of liberty is the most obvious feature in the examples of slavery that I gave you — the ancient Egyptian slave and the African slave in America. It refers to only one of the four kinds of property. But there are really many different kinds of slavery, as social philosopher, Jay Snelson, explains:

“We’ve been given a traditional view of slavery. This involves a man held in chains. If he doesn’t’ keep up with the assigned workload some brute of a slave master comes over and slashes his back with a cat o’ nine tails. The poor slave stumbles and falls to the ground. The slave master kicks him in the gut and says, ‘get up you filthy dog!’ This is the Hollywood version of slavery. Very dramatic. But [this description is] inadequate. This is a narrow and restricted view of slavery…

“It’s important to recognize you do not have to be chained up to be a slave. For example, if a thief steals your car, you have been enslaved by the thief. The thief is now in control of your car. You have lost your control [of your tangible property]. At the point in time when the thief gains control of your car, he gains control of you — and you are serving the thief. But is your service to the thief voluntary? No. You are involuntarily serving the thief. Involuntary servitude is also called ‘slavery.’ Therefore, all thieves are also enslavers.”

This quote, from a lecture recorded during the mid-1970s, highlights the close relationship between slavery and stealing. So, let’s now define the term stealing:

Stealing

The seizure of an individual’s property without his or her consent.

Note the similarity between the definitions of slavery and stealing. They are almost identical. The two terms just describe different stages of the same process. When a thief seizes your car without your consent, you have been stolen from and you have been enslaved.

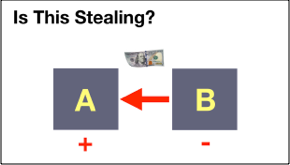

There are only two ways property can be exchanged — in other words, moved from one person’s domain of control to another. One is by seizure, the other is by consent. Here are diagrams of the two:

Let’s say I give you $1,000 and you give me a computer. We trade. It is voluntary. It is a plus-plus exchange. In this case, both A and B have gained property.

But things don’t always go this way. There can be involuntary exchanges, as well. For example, let’s say I break into your house and take your computer without permission.

In this event, A has gained while B has lost. This is stealing. It is involuntary on the part of B. It is a plus-minus exchange. Note that:

All stealing is a plus-minus exchange.

All plus-minus exchanges enslave people.

NOTE: I’m being extremely precise in the wording of these definitions for a reason. Scientific definitions are like mathematical equations. There is no room for fuzzy thinking. Terms have to be operationally precise so that when you put them into use, misinterpretation is not possible.

Go back and look at the definitions of slavery and stealing, above. Note how simple they are. That’s what scientific reasoning does, it simplifies. But now, I would like to pose a question: are stealing and slavery good for society, or are they bad?

Let’s look into this.

5.2

The ABCs of Stealing

Consider the following cases:

Case One:

There are two people, A and B, who are neighbors. Mr. B decides to leave town for a long weekend. While he is gone, his neighbor, Mr. A, smashes B’s window, breaks into the house and takes a big stack of $100 bills. Mr. A then carries them over to his own house and thinks, “Boy, this is great! Now, I can buy all sorts of stuff that I’ve been wanting.”

Using the definitions I‘ve given you, is this stealing? I am sure you’ll agree that it is, and that Mr. B has been enslaved.

Case Two:

Mr. A does not just flagrantly break into Mr. B’s house and carry off the money. Instead, he goes to Mr. C’s house, who lives in the neighborhood, knocks on his door and asks, “Is it okay with you if I take Mr. B’s cash?”

Mr. C replies, “Sure, it’s fine with me — I don’t care.”

So, with Mr. C’s consent, A then smashes B’s window, breaks in and takes the money. Is this still stealing? Has Mr. B still been enslaved? Yes, I am sure you will agree. Clearly, Mr. C is irrelevant to the exchange between A and B.

Case Three:

This time, Mr. A not only goes to Mr. C’s house to get permission, he also goes to Mr. D’s, Mr. E’s and Mr. F’s. He knocks on all their doors and asks each one of them, “Is it okay with you that I take Mr. B’s cash?”

Mr. A even organizes a neighborhood meeting and takes a vote, and the majority of the people on the block respond, “Sure, you can take B’s money. We don’t care.”

Mr. A then breaks into Mr. B’s house and carries off the stack of hundred dollar bills. Is this still stealing? And has Mr. B still been enslaved?

Case Four:

This is essentially the same as case three — except this time Mr. A is afraid that Mr. B might return home early and catch him in the act. So, after taking a vote, he hires some security guards who wear impressive black uniforms and carry military-style weapons to accompany him to Mr. B’s house. While all these hired thugs stand around and guard the street, Mr. A enters Mr. B’s house and takes the cash.

If the thieves wear uniforms, is it still stealing? Has Mr. B still been enslaved?

What if the guards fill out official paperwork, itemizing the serial number of each $100 bill?

What if A gives a percentage of B’s money to the “guards” to protect B from anybody else taking his money in the future, except A?

Do any of these circumstances change the fact that Mr. A is stealing and Mr. B is being enslaved?

By now, you may realize that I am describing how our American political system works, and how political democracies work everywhere in the world.

Our definitions of stealing and slavery seemed simple a few moments ago. In fact, they seemed so simple that an elementary school student could understand them. What has gone wrong? Could our entire political system be based on stealing and slavery? If so, how can that be? We have all been taught since childhood that stealing and slavery are wrong.

But how can they be wrong if our social system is based on them?

5.3

Do You Really Think You Know What Freedom Is?

Everyone is for freedom. It is like being for good health or prosperity or love or peace. It is a hundred percent for, zero against. This has been true through most of history. People have longed for freedom, killed for freedom, died for freedom. Even so, freedom never seems to get attained.

Politicians like to take advantage of this universal yearning for freedom. Lenin, for example, promised the Russian people freedom. He quoted Marx, and said, “You have nothing to lose but your chains!” Mao promised the Chinese people land reforms and a glorious life of freedom in his communes to rise to power. Then he created the Chinese Communist Party and became one of the biggest mass murderers in history.

During the 1960s and 70s, the United States was entangled in a war with Vietnam. Young people were drafted into the military to “fight for freedom.” On living room TVs, we watched as the jungles turn red with blood as 58 thousand Americans died along with a million Vietnamese. Today, our politicians are still lying (or confused) about it. They tell us the Vietnam “experience” was a “mistake” that “nearly tore our nation apart.” But they also say the Americans who died there did so for our freedom. But how does an American soldier dying in a war that was a “mistake” make America free? Where is the causal connection? Are we more free because young, naive soldiers went to their deaths out of blind obedience?

# #

Some politicians will hate this book. The word “freedom” is an emotional hot button, and they know it. Like the words “Constitution” or “Bible” or “America,” it strikes a poignant chord with the masses. They use those words to manipulate people — and as long as the meaning of freedom stays vague, they can use it to rationalize anything, including useless wars.

This book takes that power away.

After the next section, I will give you the scientific definition of freedom. But first, here is a collection of eleven micro-essays on popular misconceptions about what freedom is. Each one of these little essays obliterates a standard item in the politician’s toolbox.

5.4

11 Common Delusions

1. “You can attain freedom by throwing a tyrant out of power.”

People think if they can get rid of the person or system that is oppressing them, they will get freedom as a sort of residue. This has never worked. All it does is replace one tyrant (or tyranny) with another.

In the mid-1950s, for example, the island-nation of Cuba was ruled by a brutal dictator, Fulgencio Batista. He took large bribes from the U.S. based mafia, and while he dined with the upper-class in luxury, the island people lived in poverty and were controlled by a brutal police state.

Consequently, a young charismatic Fidel Castro organized a revolution. His guerrillas attacked Batista’s police from the jungles. Castro’s revolutionaries were captured, tortured, Batista held public executions and hanged the dead in the streets, including children, as a warning to others.

Batista was backed by the U.S. government which supplied him with planes, ships, tanks and napalm to protect American business interests, but to no avail. On the last day of 1958, Batista fled into exile, and Castro rolled into Havana greeted by a cheering crowd.

Castro declared himself “Comandante of the Armed Forces.” Influenced by nineteenth-century philosopher, Karl Marx, he abolished multi-party elections and declared Cuba a “socialist state.” He created the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution, a brutal police force, who sought out dissidents, arrested them, tortured them, and held executions. He appointed his comrade, Che Guevara — of bumper sticker and T-shirt fame — to be his official executioner.

Cuba went from tyranny to revolution to tyranny, and Castro became just another ruthless dictator. Today, the Castro family is simply a mafia. Yes, people can overthrow a tyrant. But unless they have a clear concept of what freedom is, all they will ever do is replace one tyrant with another.

2. “Freedom is attained by clamping down on dissidents and forcing people to adhere to your plan.”

Leaders like to think that if they can control people, then constructive social engineering can take place. This also never works.

Take Czar Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, called “Nicholas the Bloody,” a cruel dictator. To get control of his society, he gunned down hundreds of peaceful protesters in an incident called Bloody Sunday, and held mass assassinations of Jews. But it did not work. Tyranny just angers people. In response, the Bolsheviks, a political party founded by Vladimir Lenin, rose to power and assassinated him along with his entire family.

Then Lenin believed he needed to clamp down. He murdered hundreds of thousands in a period history would later call “The Red Terror.” After four years of brutality, Lenin was shot in the neck by a dissident and was replaced by Joseph Stalin who used even harsher violence to control the people. He killed tens of millions in a program called “The Great Purge.”

In Russia, one terror campaign after another was used to force people to obey. But the orderly societies the Czar and Lenin and Stalin imagined never came into existence. They just went down in history as mass murderers.

Coercion is not freedom. You cannot use despotic control to build a free society. It is a logical an operational impossibility.

3. “People should be allowed to do whatever they want just so long as they don’t hurt anybody.”

On first glance, this seems like good policy. But on close examination, it breaks down. The problem is lack of semantic precision. Consider these three statements:

“I order you to stop drinking alcohol; I’m saving you from an immoral life.”

“You will turn your land over to the State; private ownership of that land is injuring society.”

“We are going to punish the oil companies to stop climate change.”

In each of these statements, one person (or group) is enslaving another to stop them (or to stop society) from being “hurt.” These statements are typical of what well intentioned crusaders say as they set out to “protect people from harm.” (The alcohol prohibition crusader, Carrie Nation was a colorful example.) The problem with this maxim is it contains no explanation of what being “hurt” means. Therefore, it is meaningless.

4. “Freedom is individual sovereignty.”

Some libertarians believe this credo all anyone needs. If people were just self-sufficient individuals, society’s troubles would vanish. Aside from it being a hopeless attempt to change human nature, this statement is meaningless. It is an example of what, in logic, is called a circular argument.

Look at this famous example of logical circularity:

A: Where is the rake?

B: It’s next to the hoe.

A: Where is the hoe?

B: It’s next to the rake.

A: But where is the rake?

B: It’s next to the hoe.

Etc.

This is reasoning “in a circle.” A and B go around and around in a hamster wheel, never getting anywhere. Circular arguments like these are nonsensical, and the phrase,“freedom is individual sovereignty” is circular.

The term “sovereignty” is defined (by the Oxford English Dictionary) as “supreme power or authority; self-government.” What is self-government? It is the “ability to choose what you do with your life and property, i.e., being free.”

In other words, “freedom is being free.” The statement has no meaning.

5. “Democracy is freedom; people are free when they vote for their leaders.”

There are two fallacies buried in this idea. First, that political democracy, i.e. a voting system, either leads to or sustains freedom. We can deflate this notion by looking at the facts. There are countless examples of failed democracies. Haiti overflows with murders, attempted coups, poverty, corrupt presidents, worker-peasant movements, nationalization of companies, and more. If democracy is freedom, why does Haiti wallow in crime and slavery and poverty today?

Venezuela. India. Brazil. Russia. These are all democracies. And let’s not forget that Germany was a democracy when Hitler rose to power. The Weimar Republic, which had fragmented into dozens of political micro-parties, failed to stop the rising Nazi movement which, after the elections of 1932, became a popular rage. If democracy is freedom, how was Hitler able to use it to seize power?

On the other hand, Monaco, which is a paradise, is a monarchy. So is Thailand, whose capital city, Bangkok, is a thriving economy, one of the strongest in the Asian world. The only conclusion we can draw from these examples is that political democracy is not causally related to freedom at all.

The second fallacy in the slogan is that being free and being ruled by a leader is a logical and operational contradiction. Imagine, for example, you are locked up in a Super-Max prison. Yet every four years, you and your fellow inmates are allowed to vote for a new warden. Does that really make you free?

6. “There can never be freedom as long as people are unequal.”

This idea rose from the communist writings of Joseph Proudhon. Unlike Karl Marx, his contemporary, Proudhon believed in pure mutualism or, as he put it, “Everyone should be equal in dignified poverty.”

There is a flakey political movement today called “Libertarian Socialism,” and Proudhon is their philosophical founder. He envisioned a fantasy world in which no person was, in any way, above any other. The truth is, however, that nobody is equal. No two people are alike. Beethoven was a better composer than Yanni. Steve Jobs was a better entrepreneur than Bill Gates. Denise Richards is hotter than Hillary Clinton. No two people have the same skills, talent, experience or mind as anyone else, and humans will never live in a world where power, property or influence are shared equally.

7. “You are free when your view rules over all others.”

This is how some people actually feel. They think freedom only happens when they are calling the shots. These people may feel great when their opinion is the only one that matters, but what about everyone else?

Freedom, as you will soon see, is a societal concept. It has to work for all people, or it is not freedom. People who believe this idea are locked in the mindset, “For me to win, you have to lose.”

Closely related to this fallacy is the belief that…

8. “Freedom is being rich; it is having the power to do whatever you want.”

You might think if you won the lottery that would be freedom. You could buy mansions and Lamborghinis and diamond studded yachts. You could travel and never have to do anything you don’t want to do. You would wear a bank on every finger and your hands would be in every nation…

But this is just a fantasy. People dream about spending money, but not the hard work of keeping it, or how money alienates you from your friends, or how you become a target for the tax “authority,” or how huge money only comes with huge responsibility.

Having lots of money and having freedom are not the same thing.

9. “Freedom is attained through the strength of the nation.”

People have patriotic feelings towards their nation. It is a powerful emotion. But it is not the same thing as freedom.

The purpose of national imagery is to instill national pride. In America, it is the red, white and blue, the soaring eagle, the purple mountain’s majesty, George Washington crossing the Delaware. Indoctrination into our national imagery starts when we first enter school, when we are taught to memorize the Pledge of Allegiance, the Star Spangled Banner and the Preamble to the Constitution. Later, as we grow up, we see on TV brave American soldiers, heroic battles in far off lands, mighty ships patrolling the seas, quaint towns with white church steeples, glorious jets roaring over the Super Bowl.

These symbols make us feel devotion. They make us feel that America, itself, is freedom. But every nation has imagery like this. Since the beginning of civilization, leaders have used patriotic symbols to build allegiance to the state. In ancient Rome, it was Romulus and Remus and their she-wolf mother and the stately eagle. In Assyria, it was the winged sun-disk. In medieval Europe, it was the cross upon which the savior was crucified. Historian, Will Durant, explains:

“A state which should rely upon force alone would soon fall, for though men are naturally gullible they are also naturally obstinate, and power, like taxes, succeeds best when it is invisible and indirect. Hence the state, in order to maintain itself, used and forged many instruments of indoctrination – the family, the church, the school – to build in the soul of the citizen a habit of patriotic loyalty and pride … [to] prepared the public mind for that docile coherence which is indispensable in war … [for] men are more easily ruled by imagination than science.”

Does national pride create freedom? Of course not. How could politicians create freedom when they cannot explain what freedom is?

10. “There is a cost to freedom; Freedom isn’t free”

This slogan, fits nicely on bumper stickers. It claims that a “free” society requires its citizens to sacrifice. But just what is it people need to sacrifice? Money? Liberty? Their children who must go off to war? And how do we know when these sacrifices are to be made? And to whom ? A central authority?

This slogan is really just an ad campaign for the State, and for total centralized control.

Since ancient times, leaders have used a swindle called “Need, Sacrifice, Lead.” It’s a three-part rhetorical stratagem that goes, “The nation is in need. The people must sacrifice. I will lead you.” It is always an urgent appeal to “solve” some critical problem.

All a politician has to do is fill in the blanks. The “need” might be “Help the poor” or “Fight terrorism” or “Stop climate change.” Anything — and there is always an endless list — can be an urgent “need.”

The sacrifice people are called upon to make is usually, “Pay more taxes.” But it might also be “Join the military,”or “Conserve energy,” or “Submit to some new law or regulation.”

As far as where politicians are going to lead you, that does not matter. As social philosopher, Saul Alinsky, says, “A leader only needs a blurred vision of a better world.” A competent politician, in fact, should never be specific about the future because they know they need maneuvering room.

This triptych — Need, Sacrifice, Lead — has been used in every political system in every country in the world. It probably goes back to long before the time of Lagash.

Once it is parsed, the slogan “Freedom Isn’t Free” really means “Freedom is total centralized control over the people.” Which is, of course, a lie. The con game works, however, because many people cannot tell the difference between a fundamental idea and a memorable catchphrase.

11. “There is no such thing as freedom.”

This claim is usually made by so-called “sophisticated” academic types. These geniuses come from two camps. First, those who are aware that the concept of freedom has been a philosophical dilemma for hundreds of years — and because they don’t know how to resolve it, they assume a solution is impossible.

This “I can’t do it so it can’t be done” group does not realize that past failures to solve a problem do not make a problem unsolvable. The distance between the earth and the moon used to be unknown, but now it is. Tideas used to be unpredictable, but now thay are. Another famous example was the famous scientist, Simon Newcomb. Self-taught, he was able to graduate from Harvard, rise to the rank of Rear Admiral, and become a professor of mathematics at Johns Hopkins University. Nevertheless, in 1902, he claimed, “Flight by machines heavier than air is unpractical and insignificant, if not utterly impossible.” The next year, the Wright Brothers made their first flight.

Just because you don’t know how to do something yourself, doesn’t mean it can’t be done.

The second camp that claims, “There is no such thing as freedom” comes out of cognitive science. There is currently a debate in that field as to whether “free will” (i.e. “volition”), exists at all. Marvin Minsky, the A.I. scientist, claims it does not exist. We are all merely organisms reacting to random external stimuli and nothing more, he claims. His argument weakens significantly, however, when he further claims that “We have the illusion of free will so we can act morally.” Cognitive scientist, Daniel Dennett, on the other hand, argues that free will does exist and it evolves over evolutionary time.

The truth is, the inability to operationally define free will doesn’t matter. We can still create a free society as long as we know its properties. Just like we can build sophisticated electronic equipment even though nobody really knows what “an electron” is.

So, enough about what freedom is not — it is time to move on and explain what freedom is.

5.5

Ideal Freedom

Defining freedom is a two-step process. The first step is to establish a concept called ideal freedom.

Ideal Freedom

The societal condition that exists when all people have full (100%) control over their property.

In ideal freedom, people may act in any way they want, so long as their actions affect only their own property. When a person’s actions involve someone else’s property, the exchange has to be voluntary. When no one controls the property of another without consent, it follows that everyone has absolute liberty. Logically, if all people controlled their own property, and never controlled the property of another, then all forms of stealing and slavery would vanish.

Mathematician and astrophysicist, Andrew Galambos, authored this definition in 1961 — and it is well-thought out. But it has one big limitation. It can exist in theory, but not in practice.

According to a strict interpretation of the terms in this definition, ideal freedom is absolute. It is non-negotiable. If any person has less than 100% control over his or her property, then he or she is not free. Furthermore, if any society has even one person in it who has less than 100% control of his or her property, then that society is not free. In a perfect world, ideal freedom is what we would have. But the problem is, neither the world nor the people in it are perfect.

What good then is the concept of ideal freedom if it cannot exist? It is actually a crucial idea because it is a standard of measurement. It is like a concept in physics called a Carnot Engine.

A Carnot Engine is a theoretical concept. It is an ideal model that loses no energy to friction or conduction. The concept emphasizes the principles at work. The definition of ideal freedom is the same sort of thing. It’s a frictionless model, and we use the concept of ideal freedom to measure how efficiently we can make operational freedom.

All plus-minus exchanges enslave people.

5.6

Operational Freedom

The second step in defining freedom is to define operational freedom, which is the kind of freedom that exists in reality. Take a look at this graph:

The dark line at the top of the graph — one hundred percent — represents ideal freedom. Operational freedom is the gray line, and this graph shows the type of society we would all like to have, one in which operational freedom, over time, asymptotically approaches ideal freedom.

Operational freedom is created by the aggregate of voluntary interactions between people. When people control their property or exchange property voluntarily, without coercion, the result is higher operational freedom. Free World Theory technology, which will be explained in the second book of this series, is designed to increase operational freedom, as shown on this graph.

Today, however, people rely on political systems to protect their property. That doesn’t work because politicians only have the ability to coercively take property from one person (or group) and “redistribute” it to another (minus a significant handling fee). Thus, when a political system controls how you use your property, operational freedom does not go up, it goes down and approaches zero, as shown in the following graph.

Seizing property to protect it is illogical and operationally impossible.

That is why, in political systems, inconsistent events occur like FBI agents raiding people’s homes for “security.” Or the NSA recording your phone calls and texts and GPS locations to “protect freedom.” Or politicians waging wars to “ensure peace.”

You cannot use coercion to create a free world. It is impossible. Politicians try because they don’t know what else to do, and they don’t how to think clearly about what freedom is.

We define operational freedom as:

Operational Freedom

The stable, aggregate, systemic and measurable progress of society towards ideal freedom.*

*NOTE: this definition is a corollary to a more precise mathematical definition which I will give you later in this book.

In this definition, there are four vital components to operational freedom:

First, it has to be stable. This is achieved by eliminating coercive systems and replacing them with voluntary Free World Theory systems. As you do this, piece by piece, society becomes more and more operationally stable.

Second, operational freedom has to be aggregate. It must apply to the whole society. For example, you cannot have a free world in which white people approach ideal freedom, but black people do not. The definition of ideal freedom says ALL people. You cannot have a system in which rich people increase freedom while poor people lose it. Or in which politicians gain while taxpayers lose — that is the kind of system we have now, where one group gains at the expense of another.

Third, operational freedom has to be systemic. As a society eliminates coercive systems and involuntary exchanges of property, and replaces them with networks of Free World Theory systems (to be explained later) and voluntary exchanges, operational freedom becomes built-in.

Fourth, operational freedom has to be measurable. This is essential. We must be able to take accurate readings of where society stands in comparison to ideal freedom at various points in time. This is why the concept of ideal freedom is vital — data collection and statistical sampling are easy, but it is the Carnot Engine-style definition of ideal freedom that tells us what to measure, which is the protection or non-protection of property.

Finally, you may have noticed there is one big thing missing in my definitions of both ideal and operational freedom. To understand these definitions, you also have to know what property is. Without a clear, detailed, scientific explanation of property, which is intrinsic to them both, they would be meaningless.

That will be the subject of the next three chapters.

END OF CHAPTER FIVE

I like your introduction of operational, vs ideal freedom.

Thanks! The book gets better... You'll like the definition of "property."

Volume 2 is going to be called "Free World Technology." It's all about how the FWT paradigm, because it is operationally precise, can be technologized.